Suchen und Finden

A NEW IMPETUS

THE clocks in the neighbourhood had scarcely ceased striking as I ascended the steps of Kelleran's house and rang the bell. Even had he not been so impressive in his invitation there was small likelihood of my forgetting the appointment I had been waiting for it, hour by hour, with an impatience that can only be understood when I say that each one was bringing me nearer the only satisfying meal I had had since I last visited his abode.

The door was opened to me by the same faithful housekeeper who had proved herself such a ministering angel on the previous occasion. She greeted me as an old friend, but with a greater respect than she had shown when we had last talked together. This did not prevent her, however, from casting a scrutinising eye over me, as much as to say, "You look a bit more respectable, my lad, but your coat is very faded at the seams, your collar is frayed at the edge, and you sniff the smell of dinner as if you have not had a decent meal for longer than you care to think about"; all of which, had she put it into so many words, would have been perfectly true.

"Step inside," she said; "Mr. Kelleran's waiting for you in the study, I know." Then sinking her voice to a whisper she added: "There's duck and green peas for dinner, and as soon as the other gentleman arrives I shall tell cook to dish. He'll not be long now."

What answer I should have returned I cannot say, but as she finished speaking a door farther down the passage opened, and my old friend made his appearance, with the same impetuosity that always characterised him.

"Ingleby, my dear fellow," he cried, as he ran with outstretched hand to greet me, "I cannot tell you how pleased I am to see you again. It seems years since I last set eyes on you. Come in here; I want to have a good look at you. We've hundreds of things to say to each other, and heaps of questions to ask, haven't we? And, by Jove, we must look sharp about it too, for in a few minutes Nikola will be here. I asked him to come at a quarter past seven, in order that we might have a little time alone together first."

So saying, he led me into his study, the same in which I had returned to my senses after my fainting fit a few days before, and when he had done so he bade me seat myself in an easy chair.

"You can't think how good it is to see you again, Kelleran," I said, as soon as I could get in a word. "I had begun to think myself forgotten by all my friends."

"Bosh!" was his uncompromising reply. "Talk about your friends—why, you never know who they are till you're in trouble! At least, that's what I think. And, by the way, let me tell you that you do look a bit pulled down. I wonder what idiocy you've been up to since I saw you last. Tell me about it. You won't smoke a cigarette before dinner? Very good! now fire away!"

Thus encouraged, I told him in a few words all that had befallen me since we had last met. While I was talking he stood before me, his face lit up with interest, and to all intents and purposes as absorbed in my story as if it had been his own.

"Well, well, thank goodness it is all over now," he said, when I had brought my tale to a conclusion. "I think I've found you a billet that will suit you admirably, and if you play your cards well there's no saying to what it may not lead. Nikola is the most marvellous man in the world, as you will admit when you have seen him. I, for one, have never met anybody like him; and as for this new scheme of his, why, if he brings it off, I give you my word it will revolutionise Science."

I was too well acquainted with my friend's enthusiastic way of talking to be surprised at it; at the same time I was thoroughly conversant with his cleverness, and for this reason I was prepared to believe that, if he thought well of any scheme, there must be something out of the common in it.

"But what is this wonderful idea?" I asked, scarcely able to contain my longing, as the fumes of dinner penetrated to us from the regions below. "And how am I affected by it?"

"That I must leave for Dr. Nikola to tell you himself," Kelleran replied. "Let it suffice for the moment that I envy you your opportunity. I believe if I had been able to avail myself of the chance he offered me of going into it with him, I should have been compelled to sacrifice you. But there, you will hear all about it in good time, for if I am not mistaken that is his cab drawing up outside now. It is one of his peculiarities to be always punctual to the moment What do you make the right time by your watch?"

I was obliged to confess that I possessed no watch. It had been turned into the necessaries of existence long since. Kelleran must have realised what was passing in my mind, though he pretended not to have noticed it; at any rate he said, "I make it a quarter past seven to the minute, and I am prepared to wager that's our man."

A bell rang, and almost before the sound of it had died away the study door opened, and the housekeeper, with a look of awe upon her face which had not been there when she addressed me, announced "Dr. Nikola."

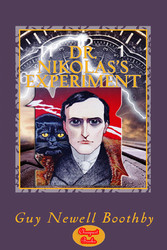

Looking back on it now, I find that, in spite of all that has happened since, my impressions of that moment are as fresh and clear as if it were but yesterday. I can see the tall, lithe figure of this extraordinary man, his sallow face, and his piercing black eyes steadfastly regarding me, as if he were trying to determine whether or not I was capable of assisting him in the work upon which he was so exhaustively engaged. Never before had I seen such eyes; they seemed to look me through and through, and to read my inmost thoughts.

"This gentleman, my dear Kelleran," he began, after they had shaken hands, and without waiting for me to be introduced to him, "should be your friend Ingleby, of whom you have so often spoken to me. How do you do, Mr. Ingleby? I don't think there is much doubt but that we shall work admirably together. You have lately been in Ashanti, I perceive."

I admitted that I had, and went on to inquire how he had become aware of it; for as Kelleran had not known it until a few minutes before, I did not see how he could be acquainted with the fact.

"It is not a very difficult thing to tell," he answered, with a smile at my astonishment, "seeing that you carry about with you the mark of a Gwato spear. If it were necessary I could tell you some more things that would surprise you: for instance, I could tell you that the man who cut the said spear out for you was an amateur at his work, that he was left-handed, that he was short-sighted, and that he was recovering from malaria at the time. All this is plain to the eye; but I see our friend Kelleran fancies his dinner is getting cold, so we had better postpone our investigations for a more convenient opportunity."

We accordingly left the study and proceeded to the dining-room. All day long I had been looking forward to that moment with the eagerness of a starving man, yet when it arrived I scarcely touched anything. If the truth must be confessed, there was something about this man that made me forget such mundane matters as mere eating and drinking. And I noticed that Nikola himself was even more abstemious. For this reason, save for the fact that he himself enjoyed it, the bountiful spread Kelleran had arranged for us was completely wasted.

During the progress of the meal no mention was made of the great experiment upon which our host had informed me Nikola was engaged. Our conversation was mainly devoted to travel. Nikola, I soon discovered, had been everywhere, and had seen everything. There appeared to be no place on the face of the habitable globe with which he was not acquainted, and of which he could not speak with the authority of an old resident. China, India, Australia, South America, North, South, East, and West Africa, were as familiar to him as Piccadilly, and it was in connection with one of the last-named Continents that a curious incident occurred.

We had been discussing various cases of catalepsy; and to illustrate an argument he was adducing, Kelleran narrated a curious instance of lethargy with which he had become acquainted in Southern Russia. While he was speaking I noticed that Nikola's face wore an expression that was partly one of derision and partly of amusement.

"I think I can furnish you with an instance that is even more extraordinary," I said, when our host had finished; and as I did so, Nikola leaned a little towards me. "In fairness to your argument, however, Kelleran, I must admit that while it comes under the same category, the malady in question confines itself almost exclusively to the black races on the West Coast of Africa."

"You refer to the Sleeping Sickness, I presume?" said Nikola, whose eyes were fixed upon me, and who was paying the greatest attention to all I said.

"Exactly—the Sleeping Sickness," I answered. "I was fortunate enough to see several instances of it when I was on the West Coast, though the one to which I am referring did not come before me personally, but was described to me by a man, a rather curious character, who happened to be in the district at the time. The negro in question, a fine healthy fellow of about twenty years of age, was servant to a Portuguese trader at Cape...

Alle Preise verstehen sich inklusive der gesetzlichen MwSt.